Contrary to what many economists believed, the eurozone has finally entered into a recession. Rising interest rates and inflation are weighing on households. Consumption is falling. Demand for new loans is contracting sharply, particularly in France. The economic cycle is coming to an end. Like déjà vu, this period of weak growth is likely to persist for several years.

Following Eurostat's revision, eurozone GDP shrank by 0.1% in the last quarter of 2022, then by the same amount in the first quarter of 2023. This is a recession, according to the definition used by international institutions - i.e., a fall in GDP over at least two consecutive quarters. This economic slowdown is mainly due to the poor German figures. Germany's GDP has fallen by 0.8% over the last two quarters. Inflation exceeded 10% last year, and remains above 6% today.

Germany penalizes Europe

During the heyday of globalization, when energy was cheap and imported goods cheap, a competitive model like Germany's was a great success. But when the global economy slowed and restructured, when geopolitical tensions involved the world's most powerful countries in one way or another, the fragilities of the German model resurfaced. The "economic miracle" of the post-World War II era is well and truly over. Since the sanitary crisis, Olaf Scholz's government has been suffering the consequences of the country's historic dependence on foreign markets, particularly Russian and Chinese.

The German economy is highly industrial (industry accounts for over 20% of value added) and particularly internationalized (exports represent 44% of GDP). Faced with rising energy prices on the one hand, and the global economic slowdown on the other, industry is suffering.

Over the past three years, factory closures have followed one another, and many companies have declared bankruptcy. The shower of subsidies orchestrated by the United States has accelerated relocation. And the development of the Chinese automotive market, particularly in the electric sector, is competing with the German automotive industry - the Achilles' heel of the country's industry. In fact, China now exports more cars than Germany. And the Middle Kingdom's stranglehold on the production of critical materials is likely to accentuate this gap.

This weakening is not just national. When Europe's engine breaks down, all European countries suffer. Not only because the country's economic activity influences that of other member states, but also because Germany has been imposing its model on other European countries for several decades. Whether in economic terms, with its emphasis on budgetary orthodoxy and an export-oriented model, or in terms of energy policy, foreign policy, migration policy, etc., the German position has always prevailed in European decision-making. And the overwhelming majority of European countries have suffered the consequences of this vision shared by Europe's big winners, the few northern countries.

The ECB continues its monetary tightening

The European economy is slowing under the impact of the ECB's monetary policy. For almost a year now, the Frankfurt-based institution has been raising interest rates in an attempt to put an end to historically high inflation. Since inflation is essentially monetary - linked to the steady rise in money supply in 2020 and 2021, when production was at a standstill due to the sanitary crisis - this policy is having an effect. After peaking at 10.6% last October, inflation is gradually coming down to around 6% today. The 2% target, set as the main objective in the European Central Bank's mandate, is still a long way off. And problems with supply chains (particularly the long lockdown in China), speculation on financial markets, the war in Ukraine affecting the European economy, and corporate margins have added new challenges for the central bank.

With the eurozone in recession, the ECB has just raised interest rates by 0.25% to a record 4% refinancing rate. It has even announced further hikes in the coming months, unlike the Fed, which is taking the liberty of leaving rates unchanged. The ECB is obliged to continue its monetary tightening to combat entrenched inflation and support the euro, which is still very weak against the dollar and therefore a source of imported inflation.

But this sharp, rapid rise in interest rates is creating a shock that economic activity is finding hard to absorb. Not only is demand for new loans contracting sharply, particularly in real estate (demand is lower than in 2007), but production and investment are also slowing down, which should ultimately lead to higher unemployment.

This policy also accentuates the gap between the real economy and the financial sphere.

Until now, the ECB has only slightly and gradually reduced its balance sheet, while orchestrating an historic rise in interest rates. Unlike households and businesses, banks and financial institutions benefit from liquidity support in central bank money (as demonstrated by the banking crisis last March), despite the rising cost of credit. So it's hardly surprising that markets remain on an upward trend... Especially as the Fed, which determines the cost of most of the world's borrowing, has decided to pause its interest rate hikes after massively supporting the sector in previous months.

Nevertheless, the ECB has indicated in its latest press release that it will stop reinvesting certain maturing bonds from July onwards. As a result, the ECB's balance sheet will shrink further, which could have a negative impact on the eurozone's financial system. The ECB is seeking to progressively fight inflation while avoiding a banking crisis, which seems impossible.

What is the future of the eurozone?

In the short term, the eurozone should see a further contraction in GDP in the next quarter. The index used to measure activity in the manufacturing and services sectors in the eurozone has fallen to an extremely low level, below estimates. This sector, which has been doing well until now, shows that European economic activity remains very fragile. On the face of it, this development could prompt the ECB to be less aggressive in its monetary tightening at the July meeting. Indeed, this is what the markets believe, since long rates fell in the wake of these announcements. However, this scenario is unlikely to materialize, as inflation remains very high, and a change in policy would cause the euro to depreciate against the dollar, helping to sustain inflation. As a result, price rises will continue to slow in the months ahead, as shown by the trend in producer prices, but will drag growth down with them.

In the medium to long term, European countries could experience several years of sluggish growth. The Old Continent continues to suffer from divergent interests among its member states, and from a structure that is not adapted to them. Moreover, the interference of foreign powers nips in the bud the possibility of moving towards a different model. As long as these aspects persist, it remains utopian to speak of a possible European renewal. In tomorrow's world, however, the stakes are high. New powers are emerging and alliances are being forged. The continent's singular qualities - particularly cultural, intellectual and economic - would enable Europe to position itself as a leader in many fields.

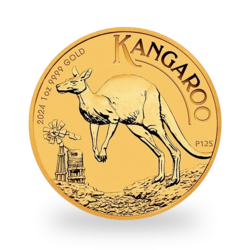

Gold in times of recession

In times of recession, gold has always been seen as a safe-haven asset to hedge against the risk of falling markets. For over half a century and in most cases, its price has risen during periods of recession. Particularly during the subprime crisis, the yellow metal was highly attractive: demand kept rising, and its price doubled in four years (between 2007 and 2011).

The contraction of economic activity in 2020 also led to a surge in demand, enabling gold to reach a new high. And the return of inflation in 2021 has continually driven gold higher to this day. With the current recession coupled with high inflation, demand for gold is set to rise all the more.

As for silver, the outlook remains uncertain. Although its price also rose drastically during the 2007-2008 crisis, silver performs less well overall during recessions. Over the past five decades, its price has outperformed the S&P 500 in only three of the eight recessions: 1973, 1981 and 2007. The silver market remains particularly volatile due to its smaller size. As silver is used in many industrial products (particularly in the energy sector: nuclear reactors, solar panels, etc.), a downturn in economic activity is always likely to have unexpected effects on the silver price.

In the short to medium term, gold should at least continue its upward trend. Persistent inflation in Western economies, geopolitical tensions, the global economic slowdown and the return of protectionism all suggest that demand will continue to rise in the months ahead. These are global phenomena, and by extension, they are encouraging all international investors to turn to the yellow metal.

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.