The interest rate hikes implemented by central banks since the resurgence of inflation have appeared to be the norm. However, it is a revolution in the making. After decades of falling rates, they are now rising sharply, raising fears of unprecedented financial and economic risks. But what does the interest rate really mean? How important is it to the economy? How did we get here? What conclusions can we draw? These are the questions we seek to answer here.

The interest rate is often defined as the cost of risk. When an individual lends 100 to another, he wants the latter to return more than the sum loaned, thus monetizing the risk of the loan. This rate therefore represents the creditor's degree of confidence in the debtor's ability to repay.

From another angle, some define the interest rate as the price of time, because the interest the borrower has to pay back requires him to do extra work to repay the sum. Which, by definition, requires working time. Obviously, today more than ever, the creditor plays on this advantage and the borrower's impatience for business.

Centuries ago, the interest rate was simply defined by an agreement between two individuals, but as the economy became more financialized, it was determined by the market. Today, interest rates are determined by the central bank, which sets the key rates at which banks borrow and to which the market refers.

How important is the interest rate to the economy?

Today, money is exclusively debt. It is in fact created by commercial banks when they distribute loans, particularly real estate loans (representing over 60% of outstanding loans), but also by the central bank (although this so-called "central" money circulates only in the interbank market).

In fact, interest rates exert a significant influence on the money supply, whose evolution has an impact on economic activity. Theoretically, falling interest rates encourage borrowing, and therefore the creation of more money (whether through a loan taken out by a household for a personal asset, or by a company to expand, or by a government to spend, etc.). To a certain degree - the preference for saving - the economy is stimulated.

Conversely, rising interest rates restrict demand for credit from economic agents who anticipate more costly debt servicing. As a result, money creation slows down, investment and consumption are likely to decline, and the economy may suffer as a result.

So why do rates keep falling until they reach negative levels, when they averaged around 5% over the last few centuries? There are many reasons for this.

The start of a long cycle

The great cycle of falling interest rates began in the 1980s. At that time, after two oil shocks had led to unprecedented price rises, it was time for economic recovery and globalization. The world opened up, international trade intensified, and financial liberalization measures were introduced worldwide. In the United States, President Reagan embodied this ideology to the full, reducing public regulation and cutting federal income and capital gains taxes. In addition, central banks became independent, with the primary objective of maintaining inflation at 2% to avoid another inflationary crisis.

The U.S. Federal Reserve, which had just sharply raised interest rates, decided to lower them to stimulate the U.S. economy. The other central banks followed this policy to limit potential exchange-rate differentials with the dollar (the world's reserve and trading currency since 1945), since too great an appreciation of their currencies could harm their competitiveness.

Against this backdrop, inflation stabilized at around 2-3% over the following decades, which was the desired target. However, structural factors were driving prices down, notably demographic aging (leading to a slowdown in consumption and investment) and globalization, resulting in a large workforce (particularly in China) and extremely low wages in many countries.

To keep inflation close to 2%, monetary policies became increasingly flexible. Interest rates were lowered, leading to an overall increase in money creation, which had been without physical limit since 1971. This date marked the end of gold-dollar convertibility, i.e. the ability to create money with no gold equivalent available to central banks.

Financial globalization led to a race for growth between countries, resulting in disruptive innovations (in technology, science, space, medicine, etc.), but also in the rapid development of deadly industries. In short, it was a time when anything was possible, thanks to an unprecedented method of money creation.

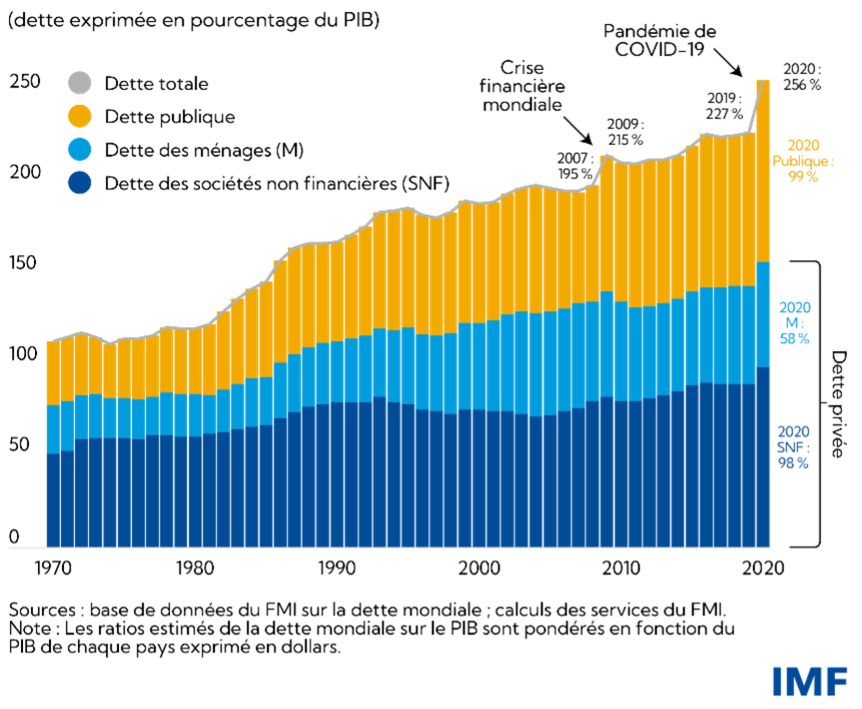

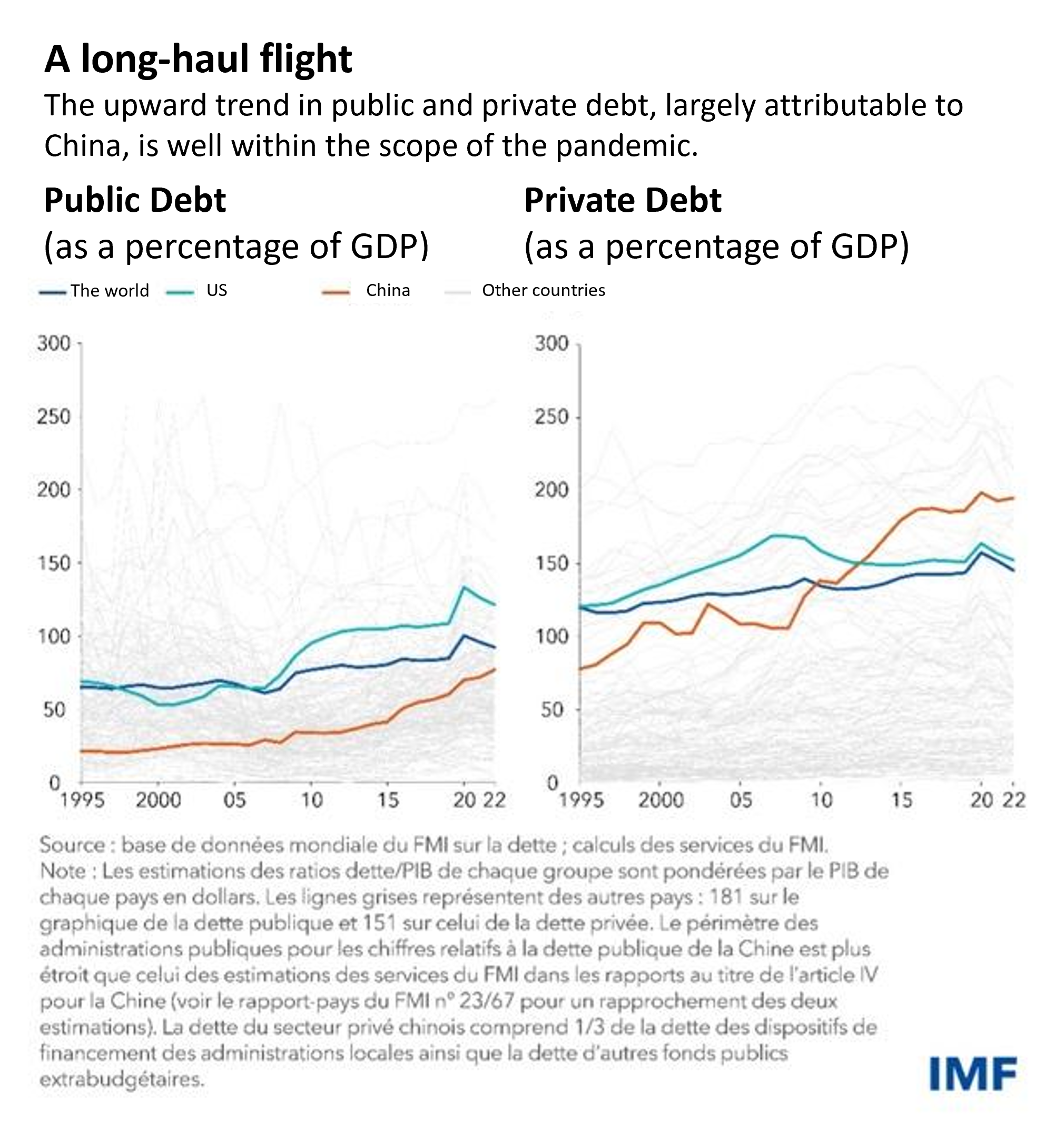

These strong periods of growth were also marked by the appearance of economic and financial crises every five to ten years (the 1987 and 1994 bond crashes, the 1997 Asian crisis, the 2000 internet bubble, etc.). However, their effects were mitigated by the support of central banks, whose role it is to ensure market liquidity when financial instability is felt. With each crisis, key interest rates were lowered once again, and liquidity was plentiful. From 10% in 1984, the US Federal Reserve's main rate fell to 4% in 2001. Global public and private debt continued to rise sharply, while inflation remained under control.

Following the bursting of the dotcom bubble in 2000, financial engineering began to flourish, and sophisticated financial products emerged, notably securities backed by thousands of mortgages. The economy gradually became hyper-financialized. At the same time, banking concentration intensified, as debt and leverage became easier for solvent companies with strong market power, enabling them to buy up smaller companies. Financial conditions fed speculation. Conversely, productive investment became increasingly rare.

When the US economy slowed and inflation rose in 2005-2006, the Fed raised rates slightly to attract foreign capital and maintain price stability. What happened next is well known: subprime mortgages came to light, and a real estate crisis hit the world. The measures to be taken were colossal, given the high stakes for the economy. The US Federal Reserve abruptly cut interest rates (from 5% in September 2007 to 0% in December 2008!), and public authorities bailed out financial institutions to cover their losses. As the public debt of countries hit by the crisis soared, the risk was passed onto future generations.

Thus, until 2021, rates were kept close to zero in order to avoid a bursting of the financial bubble. Under these conditions, economic agents (households, companies, governments) took on debt in amounts that were often out of all proportion to their ability to repay. This is a historic period, with interest rates going negative for the most powerful players (multinationals first and foremost), who were taking advantage of the situation. As Coluche once said: "The rich borrow, the poor repay". These players repay their previous debts by taking out new loans, which the central banks then buy back on the secondary market to support them, thus artificially maintaining the markets. The result: the price of financial assets continued to rise, and wealth inequalities increased substantially.

This system is showing its limits more than ever during the health crisis, when central bank support is such that financial markets and the real economy move in opposite directions.

The order of things always prevails in the end

In 2021, the promise of a better world embodied in globalization had become an obvious illusion in the collective unconscious. Protectionism was re-emerging, international trade was slowing, war was hitting Europe, growth was weakening, the need for profit was at an all-time high, and inflation was spiraling out of control.

After denying reality and declaring that the rise in prices would be "transitory", central banks faced up to the situation: inflation exceeded 10% and threatened to spiral out of control. Monetary institutions were forced to tighten their policies to maintain price stability and preserve confidence in the currency... However, public and private debt reached an all-time high as a result of the measures implemented over the last forty years.

In September 2023, global debt reached a record $307 trillion. This time bomb was ready to explode: what was to be done? Some were calling for a clean slate (debt cancellation), others for austerity (cutting public spending and raising taxes) to preserve the status quo.

Monetary institutions had another solution: to raise rates while keeping them below inflation so that financial conditions remain accommodating. Moreover, following signs of financial instability marked by the collapse of US regional banks and the giant Credit Suisse, the Fed was justifying the implementation of a new, unprecedented program1 to provide liquidity to the interbank market, at a time when confidence was being eroded by accumulated losses. The situation is still under control.

In the West, interest rates only became higher than inflation from mid-2023. However, the real impact of these increases is felt a year and a half later (despite this, growth slows and unemployment rises). In the meantime, companies are drawing on their cash flow to pay interest and finance their spending, many households are forced to take on debt to maintain their consumption levels, and governments are cutting back on public spending as the burden of debt gradually becomes the biggest item on their budgets. After several decades in these configurations, the change is brutal, but progressive. The interest rate revolution has begun. The great cycle of falling interest rates is gradually turning around...

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.