For several months now, we have highlighted the threat posed by rising interest rates to the US government budget. Faced with a debt wall, the Treasury will have to significantly increase the amount it borrows on the markets. The U.S. government faces the same problem as a variable-rate borrower whose repayments increase overnight when interest rates rise sharply.

In theory, the situations may seem similar. However, it is clear that a government is not in the same position as an individual borrower subject to a variable rate. A state has the ability to turn the printing press when it finds itself in this type of trap. Thus, the debt wall does not have the same meaning for a state as it does for an individual or a small business.

A private debt problem poses greater challenges to the economy than a public debt problem.

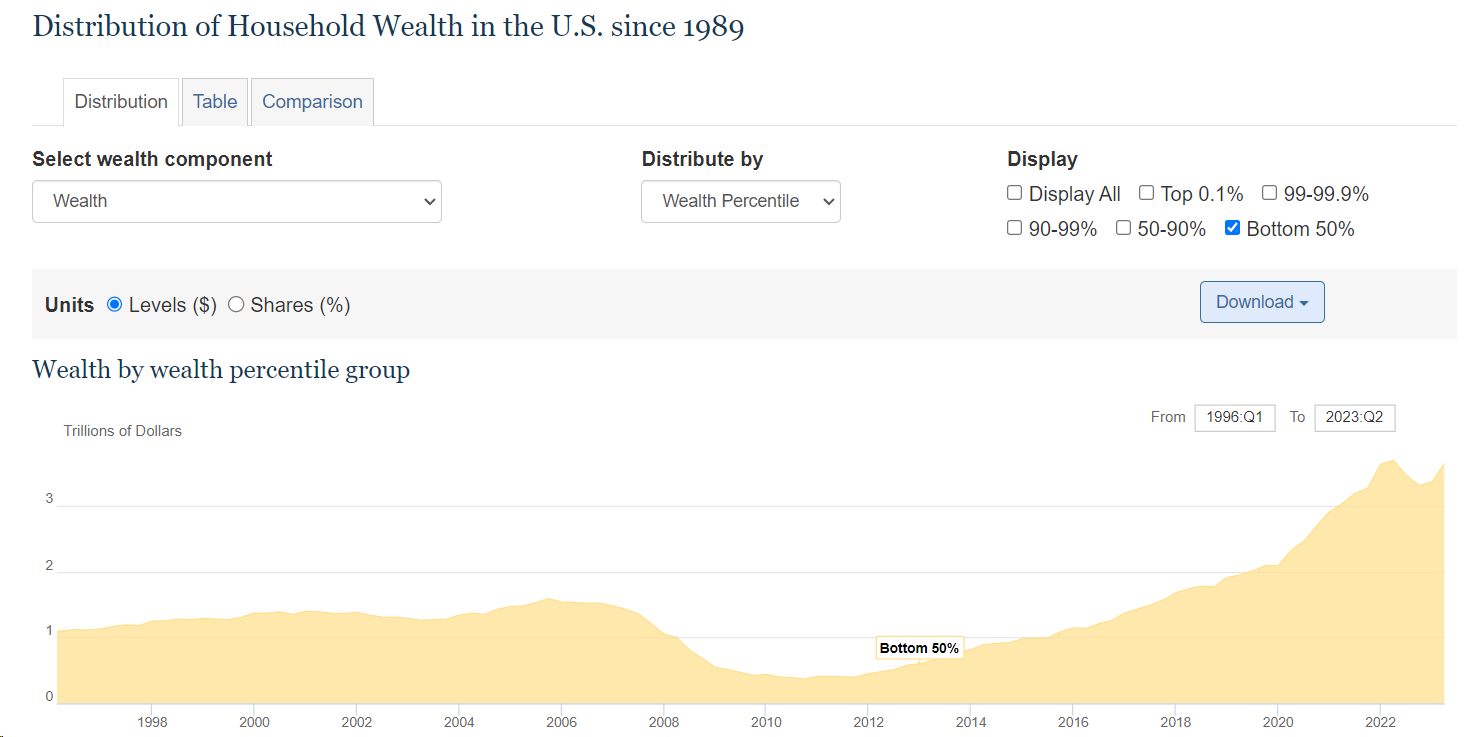

Last month, the U.S. Federal Reserve released a study assessing the increase in the population's wealth by comparing different income categories. The first finding of this study is that, over the course of the century, income disparities have continued to widen in the United States. Wealth is increasingly concentrated among the wealthiest 1%, who have barely felt the impact of recent recessions and have benefited more from the rise in asset values stimulated by the US low interest rate policy.

The other surprising finding of this study is that, although the poorest Americans were the first to feel the effects of the great recession induced by the 2008 financial crisis, the Covid-19 crisis did not affect them in a similar way. Support measures enabled them to resist better than in 2008.

The U.S. middle class seems to be much less affected than in 2008, which puts the Fed in a totally different position compared to that period.

Unfortunately, however, this observation does not take into account inflation, which is having a more significant impact on the poorer classes.

It would be a mistake to ignore inflation. However, by focusing solely on the raw data, without taking inflation into account, we tend to perceive a difference in the situation compared to 2008.

The real estate crisis hit the poorest hardest, as they held subprime mortgages that plunged them into huge financial difficulties when interest rates rose.

This time around, even the most modest homeowners have negotiated fixed-rate loans, and the increase in rates is not having the same impact as during the last real estate crisis.

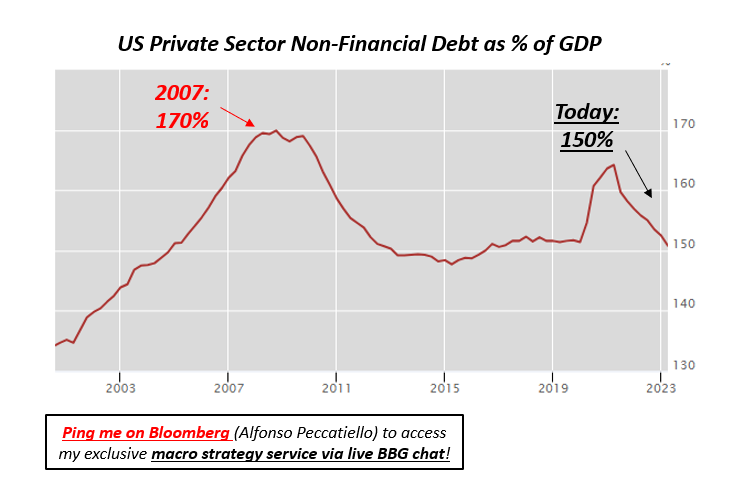

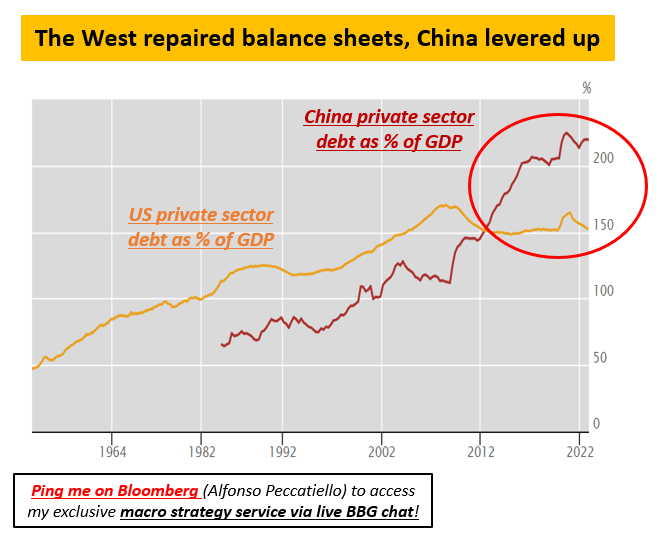

Economist Alfonso Peccatiello has studied the weight of private debt worldwide. In the United States, the private sector is certainly indebted, but the situation is far from resembling that of 2007. Currently, private non-financial sector debt represents around 150% of GDP:

Although the level of private debt may seem significant, it remains well below the warning thresholds that have triggered major crises in the past.

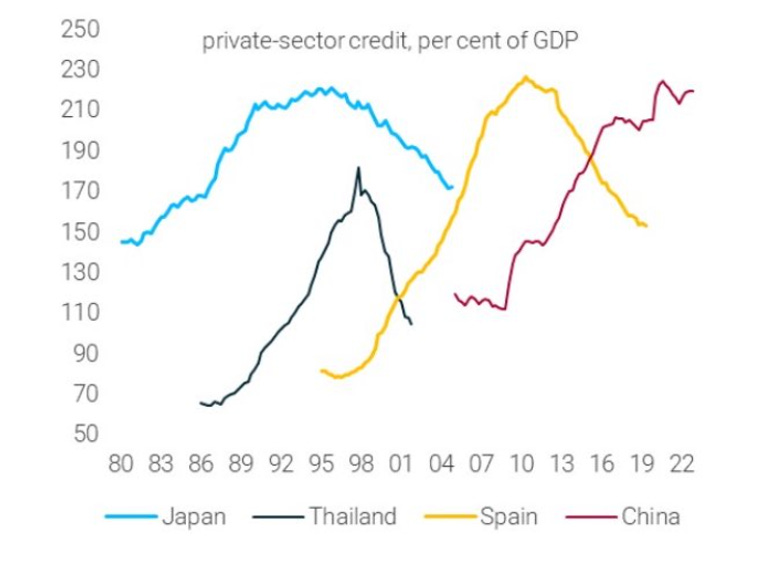

In the 1990s, Japan's private debt exceeded 200%. Thailand was approaching these levels at the time of the Asian crisis, and Spain also reached levels close to 200% during the 2011 sovereign crisis.

Today, many countries other than the United States find themselves in even more uncomfortable situations.

China, for example, faces a much larger private debt problem:

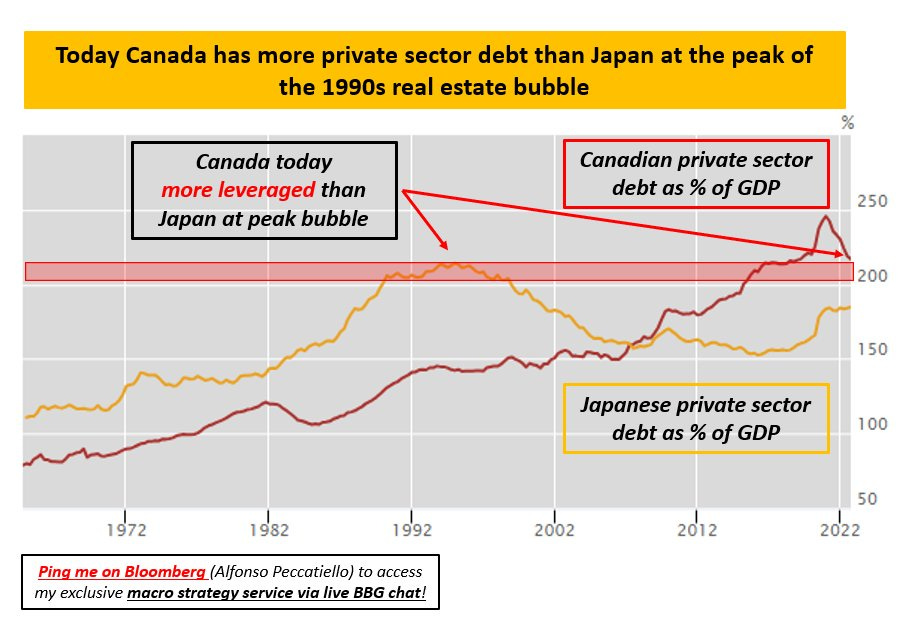

The situation is also tense in Canada, where households have taken out much larger loans than elsewhere, particularly at variable rates. The size of the debt held by the private sector is far too large in relation to the country's GDP, and the very nature of this debt, requiring very short-term refinancing at considerably higher costs, puts Canada in a perilous situation economically.

This situation, less worrying than during the last financial crisis, seems to be the reason behind the Federal Reserve's measured stance, as it does not feel a pressing need to bend its monetary policy. The effects of rising rates have not had a devastating impact on the middle classes, at least for the time being.

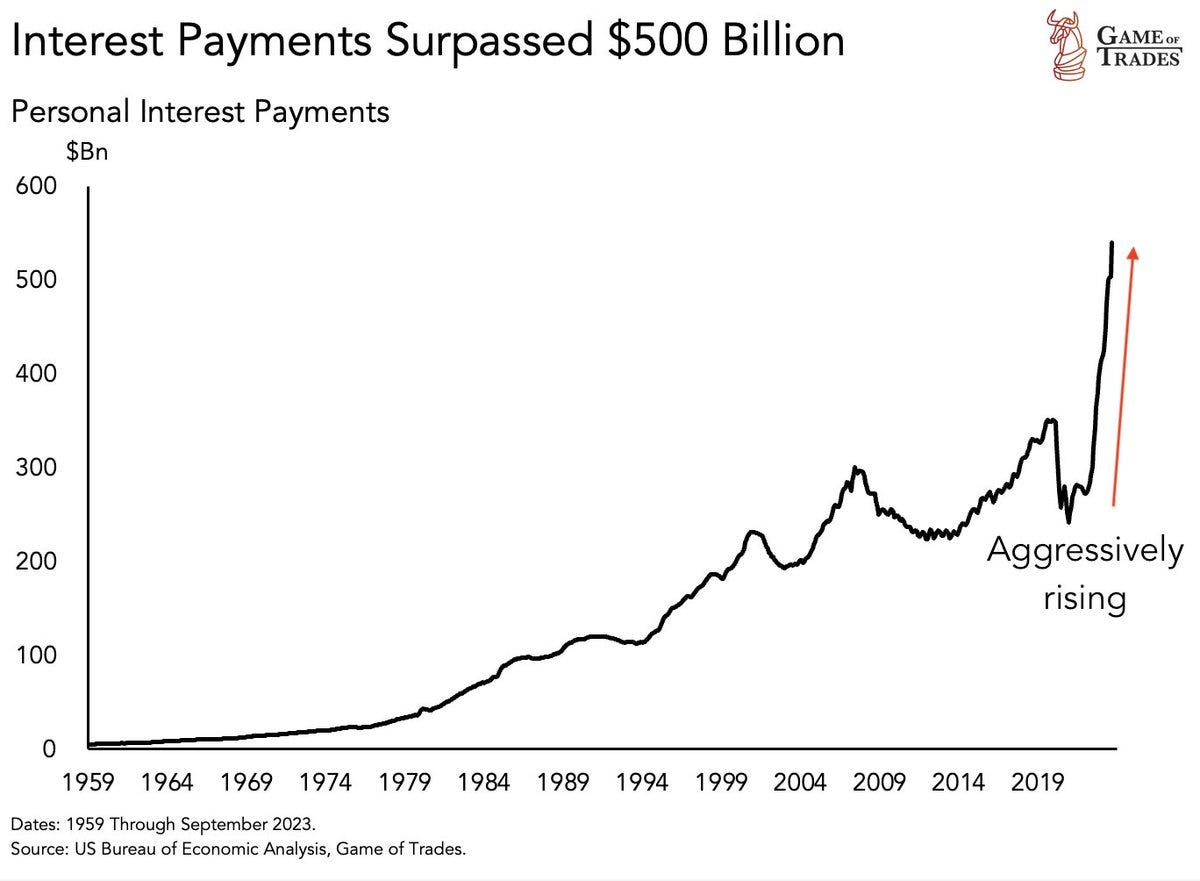

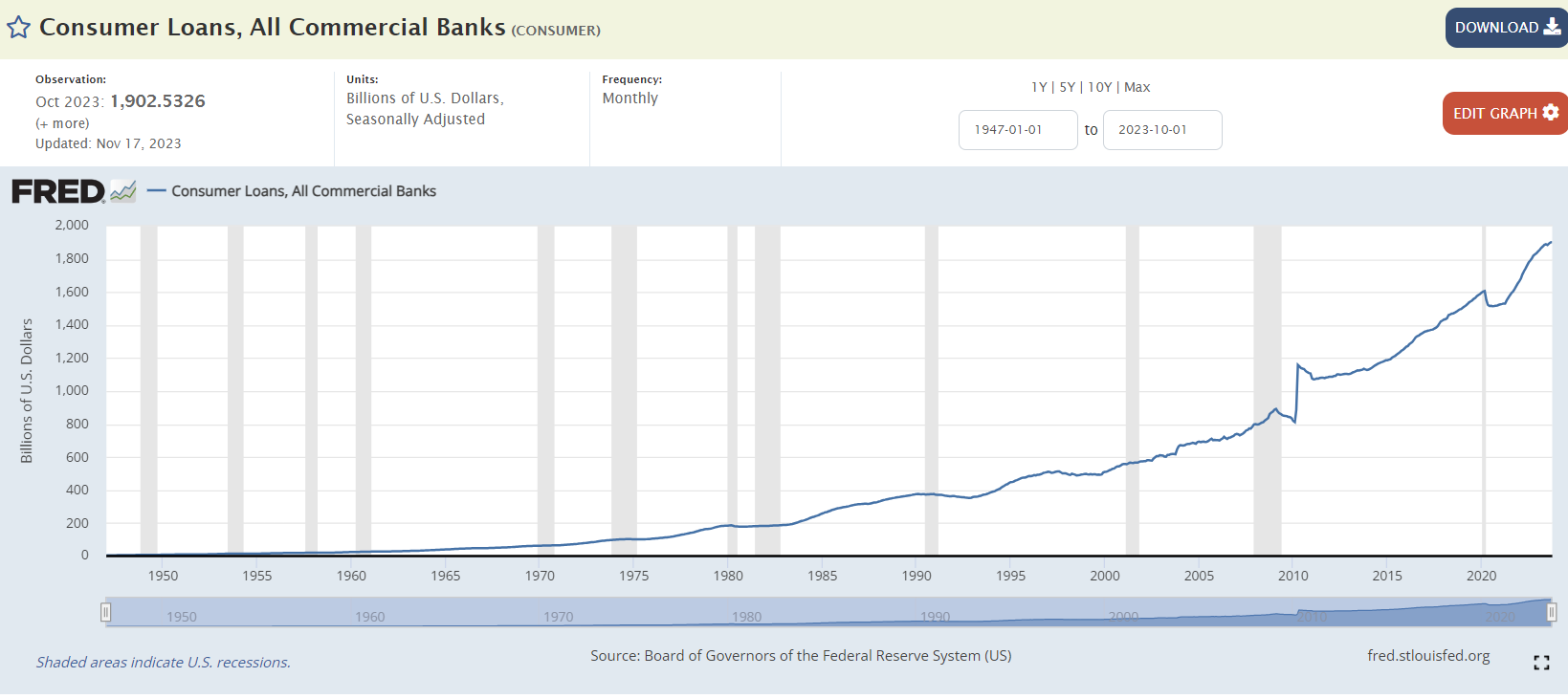

Although US households are less affected than in 2008 by their real estate debts, one sector is beginning to give cause for concern: consumer spending. The rising cost of interest on personal loans has skyrocketed since interest rates were raised. To cope with inflation, American households are increasingly turning to their credit cards, and even if the level of late payments has not yet reached alarming levels, the amount of interest on these loans has never been so high:

The level of consumer credit has exploded in recent years:

In 2008, the private credit bubble was linked to real estate, whereas today, the credit bubble is linked to consumer credit. Even if, on the whole, the Fed may feel that credit risk in the private debt sector is lower than in 2008, the lag effect could pose a real problem as early as next year in the consumer credit sector.

Not only does this new bubble present a risk for debt issuers, but its bursting would have a very negative impact on American consumption, which represents the last and only engine of growth on the other side of the Atlantic. This type of credit event is very difficult to correct once it occurs. Even with a rate cut, the inertia of the slowdown hampers the possibility of having an immediate effect when the bubble bursts.

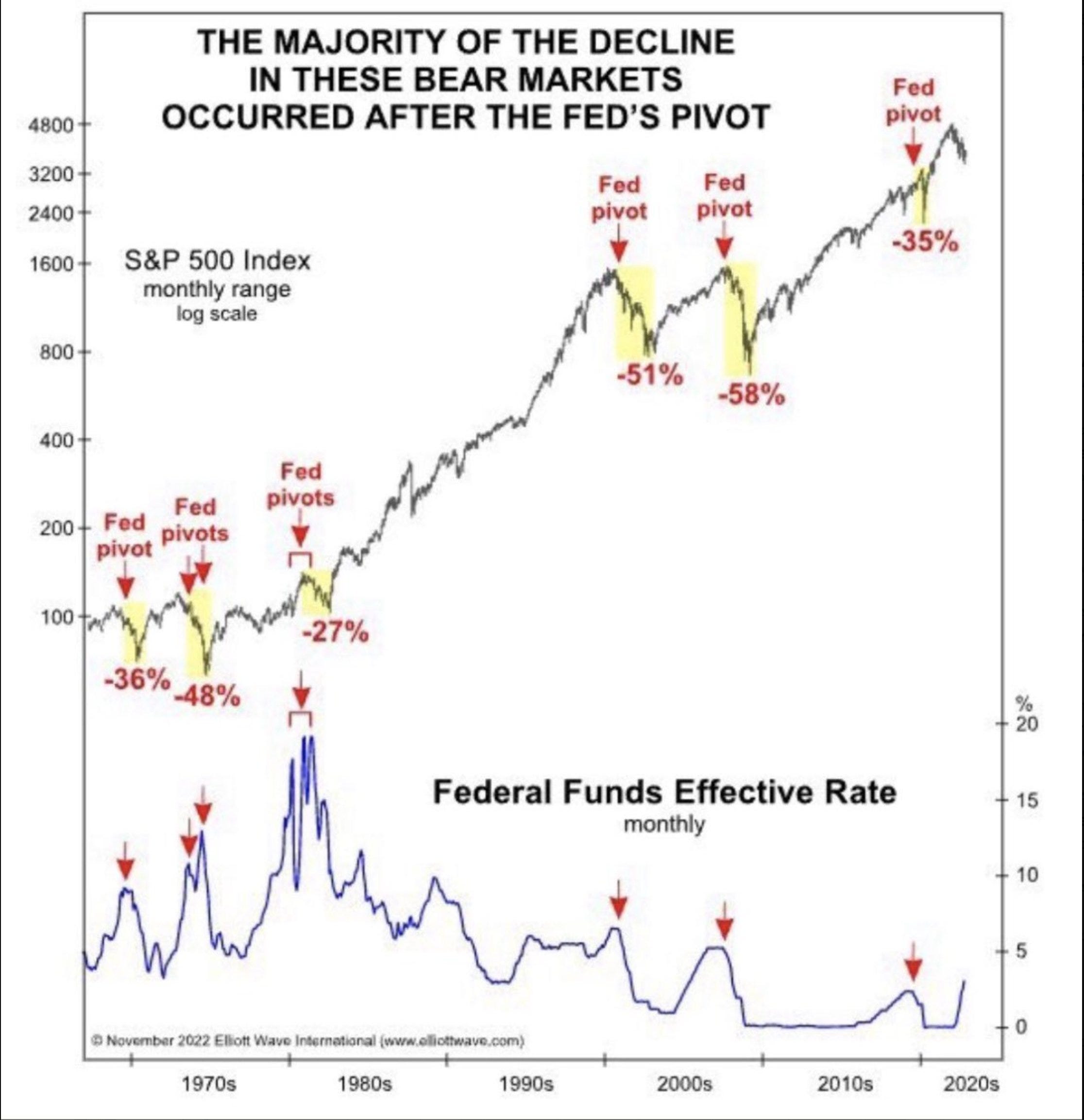

It's also crucial to note that U.S. recessions have almost systematically occurred after the Fed has changed course. Market corrections occurred after, not before, monetary policy adjustments:

What's different about this crisis, compared with previous private debt crises, is that this time the bond market is not at all in the same configuration as in previous crises.

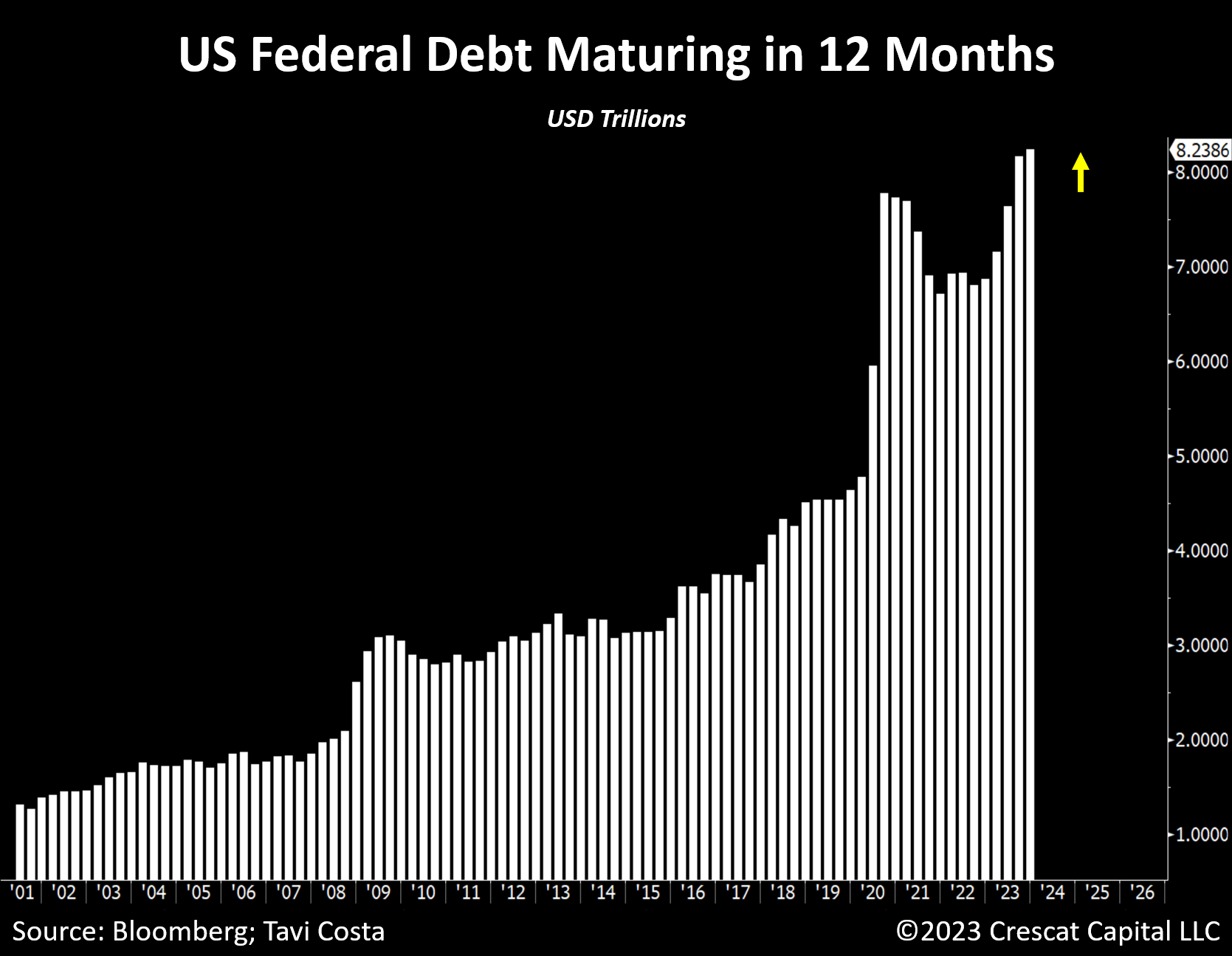

Today, the private debt market is in fierce competition with the public debt market. The US government will have to refinance no less than $8.2 trillion in debt over the next twelve months alone! And then, of course, there are the new issues that will have to make up for the ever-growing US deficit.

At the same time, private issuers will need to significantly increase their debt issuance in 2024. The most risky issuers in particular will be the most likely to tap the market to refinance their own debt.

The quantity of products classified as speculative in these new issues is set to triple by 2025:

How to refinance in an environment where the US Treasury is cannibalizing bond demand?

This time, private debt issuers are in direct competition with a government that is likely to capture a very large proportion of bond demand.

Even if the situation regarding private debt is not problematic at the moment, 2024 is likely to be a very different story: the wall of private debt is much harder to break through than the wall of public debt.

These U.S. debt risks are the main reasons why gold prices are so high. The closer we get to the debt wall, the more gold becomes a tangible indicator of risk.

Historically, gold tends to be relatively stable in pre-election years. However, as 2023 draws to a close, we find ourselves in a very special situation. The debt wall that is clearly looming ahead of us is changing the game, and the risk of a breakout in gold is becoming increasingly important, even in the short term.

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.